Samarkand Visit Guide: Travelling Through Silk Road Splendour

This visit guide covers my trip to the ancient Silk Road city of Samarkand in Uzbekistan.

Samarkand visit

Ah Samarkand! At last, after an interesting ride on the Shark train from Tashkent, I had arrived in this city.

As I already wrote in the trip report introduction, I had long wished to visit Uzbekistan and one of the main reasons why is the purported beauty of Samarkand.

The name of Samarkand alone evokes Silk Road riches, fabulous Islamic art and a sense of adventure.

In the 14th century, the city of Samarkand, which had been sacked by the Mongol horde of Genghis Khan more than a century earlier, witnessed a remarkable transformation.

Timur, a local ruler from the nearby city of Shakhrisabz, made Samarkand his new capital city.

From Samarkand, Timur (also known as Tamerlane in English) managed to carve out an enormous empire that stretched from Turkey to China at its heyday, bringing tremendous wealth to the city.

Under the reign of Timur’s grandson, Ulughbek, and the subsequent Shaybanid rulers, further monuments were constructed in the city.

Golden road to Samarkand

Despite being the former capital of a once-mighty empire, traveling to Samarkand feels like you are embarking on a trip into the unexplored depths of a remote corner of the world.

Even though I was fully aware of the beauty that awaited me, I couldn’t help but feel an immense sense of anticipation as I made my way from the train station to the Registan, the main sight of Samarkand.

In his renowned 1913 poem “The Golden Journey to Samarkand,” British novelist James Elroy Flecker eloquently captured a similar spirit:

We travel not for trafficking alone.

By hotter winds our fiery hearts are fanned.

For lust of knowing what should not be known

We take the Golden Road to Samarkand.

Writing these lines, which I know by heart, once again gave me goose bumps as I recall the unforgettable moment of setting foot on Registan Square for the very first time.

Visiting the Registan

The madrassas of Samarkand’s Registan are three exceptional masterpieces of Islamic architecture and art and rightfully holds its place on the prestigious UNESCO World Heritage List.

The Registan also acted as Samarkand’s bustling commercial centre.

What is now an empty square was likely full of market stalls and bustling bazaars during the medieval era.

If you stand in front of the square, you will see from the Ulughbek Madrassa on your left, the Tilla-Kari Madrasa in the middle and the Sher Dor Madrassa on your right.

I started off my Registan visit in earnest by exploring the Ulughbek Madrassa on this rainy day in Samarkand.

Inside the Ulughbek Madrassa

Just like the other buildings on the Registan, the Ulughbek Madrassa was used as an Islamic school.

Besides receiving a religious education, students also were taught subjects like mathematics and astronomy.

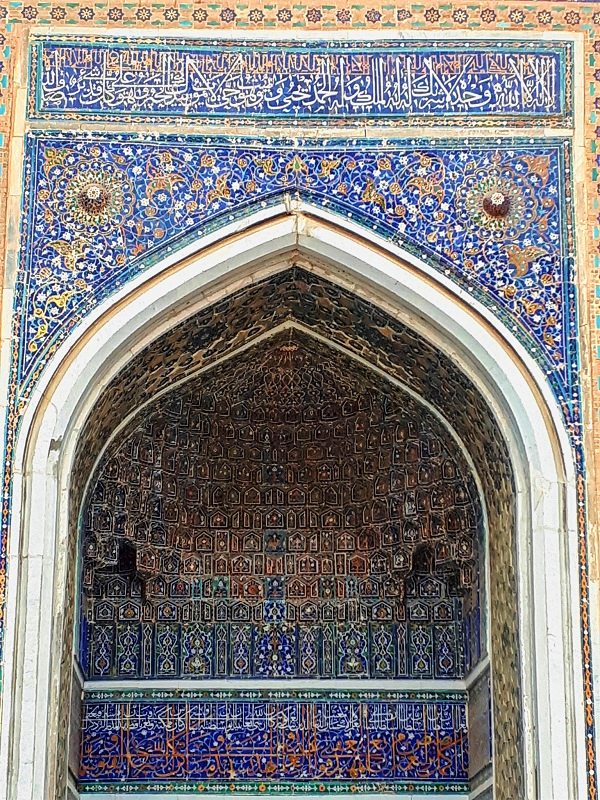

Similar to the other two structures on the Registan, the entrance to the Ulughbek Madrassa is highly impressive in both size and beauty, featuring exquisite blue tiles adorned with intricate Islamic calligraphy.

A smaller hallway leads to the inner courtyard of the building, which was completed in 1420 during the reign of Ulughbek, the grandson of Timur after whom it is named.

The students resided in dormitory cells that lined the interior courtyard, prayed in the madrassa’s own mosque and studied in lecture halls.

In present times, most of these dormitory cells have been repurposed as souvenir shops, while others remain closed with their wooden doors tightly shut.

Climbing the minaret

While I was exploring the madrassa, a friendly shopkeeper approached me and asked whether I would like to climb up one of the minarets.

For $2 or so in baksheesh he discreetly opened a couple of small doors with his keys and told me to walk up the stairs.

He also instructed me to keep my head lowered, not only due to the low ceiling but also to avoid being noticed by others in the vicinity, as it became apparent that he was technically not permitted to allow visitors to climb up the minaret.

The views from the top of the 33-metre-high minaret were absolutely worth it, as I not only enjoyed sweeping views over the Registan but also could admire the Bibi Khanym mosque in the distance.

Tilla-Kari Madrassa

The second building on the Registan (the ‘middle’ one) that I visited was the Tilla-Kari Madrassa, constructed in the year 1660.

The name Tilla-Kari Madrassa apparently means something like “gold-covered madrassa”.

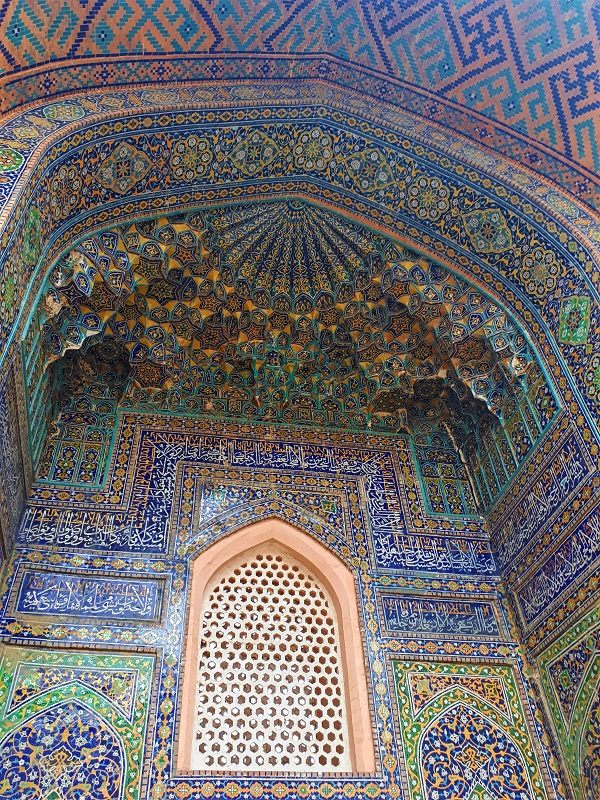

Characterised by a predominantly blue-colours tiles on its exterior, the Tilla-Kari Madrassa truly lives up to its name as the “gold-covered” madrassa once you step inside.

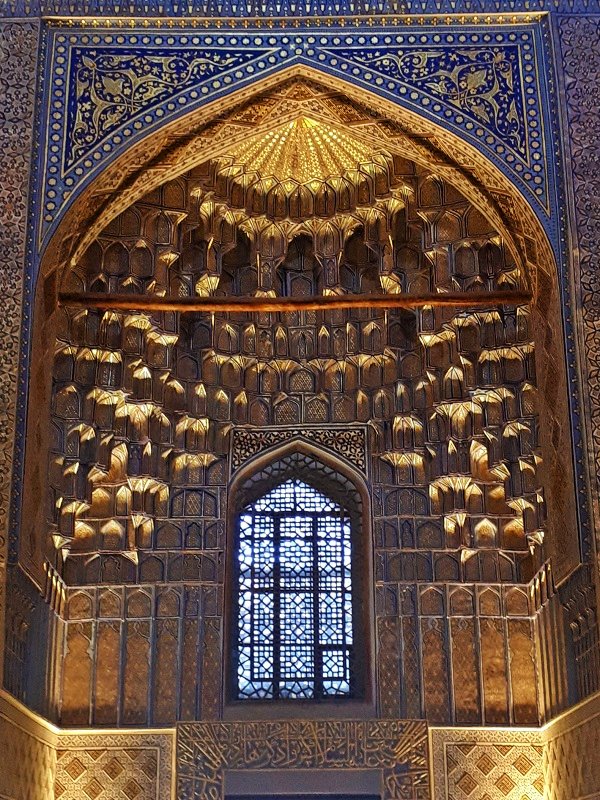

The interior of the Tilla-Kari Madrassa is decorated with so much gold that it can almost be blinding.

The gold does however blend brilliantly with the blue tiles, creating some absolutely stunning visual effects.

From the interior courtyard you have a good view of the equally beautiful but oddly shaped azure blue dome of the Tilla-Kari Madrassa.

Sher Dor Madrassa

The Sher Dor Madrassa was the last of the three Registan madrassas I had the opportunity to visit in Samarkand.

The name of this madrassa built in 1636 basically means “Lions’ Madrassa” and on the façade you can therefore see the image of two lions.

This madrassa is undeniably stunning too, although I couldn’t help but notice that the two depicted animals bear a closer resemblance to tigers rather than lions.

No amount of pictures or words can truly capture the immense beauty of the Registan.

Personally, I believe that the Registan in Samarkand should be among the top-ranked buildings in the world that one must visit in their lifetime, alongside such places as Cambodia’s Angkor Wat or the Acropolis in Athens.

Dinner

To end day one in Samarkand I had a lovely dinner of manti (steamed dumplings filled with meat) and plov (Uzbekistan’s national dish, slowly cooked rice dish with meat, carrots and onions) at a restaurant near the Registan.

The entire meal, including a bottle of water, salad as well as complimentary tea, amounted to no more than 4 euro.

Even though I had tremendously enjoyed my visit to the Registan, little did I know that Samarkand had so many more beautiful sights to offer the next day.

Timur’s mausoleum

I started the second day of my Samarkand trip with a visit to the Guri Amir Mausoleum, the final resting place of Timur.

According to the tales of yore, Timur had expressed his desire to be buried in his birthplace of Shakhrisabz.

However, after he unexpectedly died from pneumonia during a severe winter, Timur’s remains could not be transported over the mountain pass towards Shakhrisabz, which meant that he had to be buried in Samarkand instead.

The mausoleum holds significant architectural importance, as it served as inspiration for some famous Mughal structures on the Indian subcontinent, including notable landmarks like Humayun’s Tomb in Delhi and even the iconic Taj Mahal in Agra.

The name Guri Amir aptly translates to “Tomb of the King” in Persian.

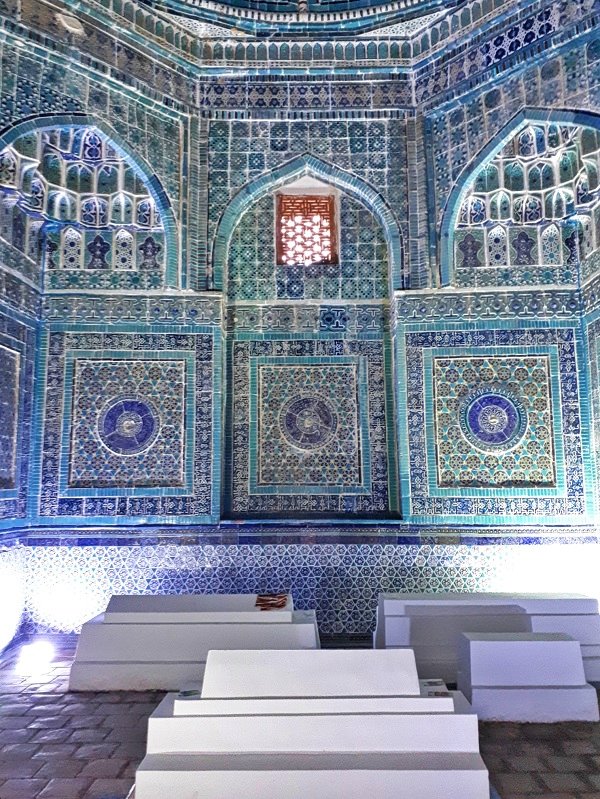

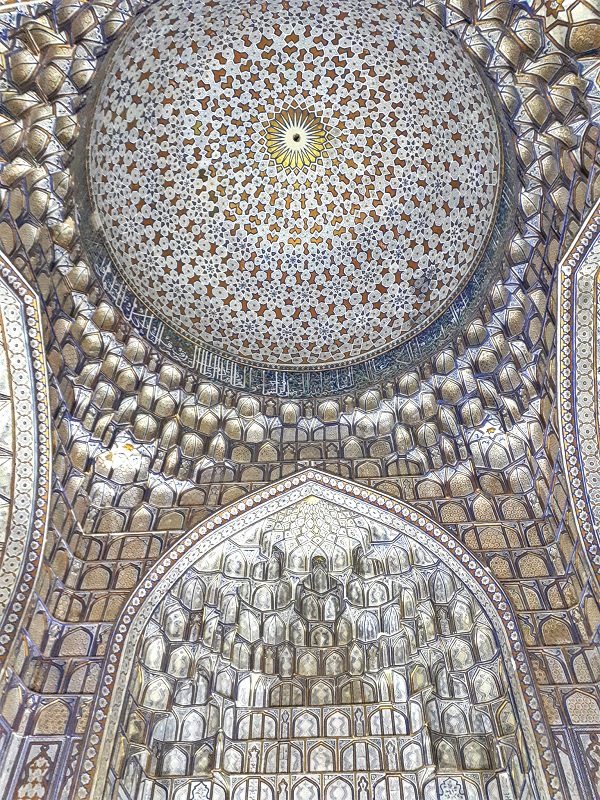

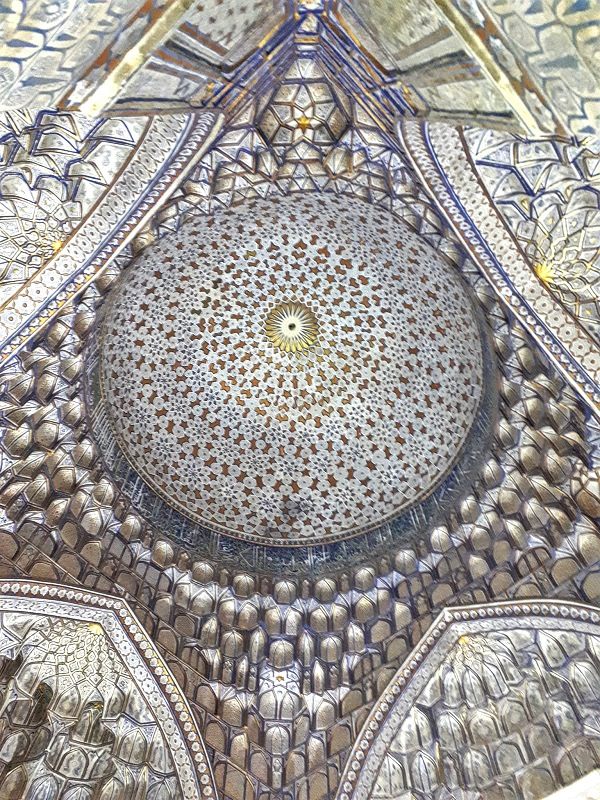

Inside the mausoleum

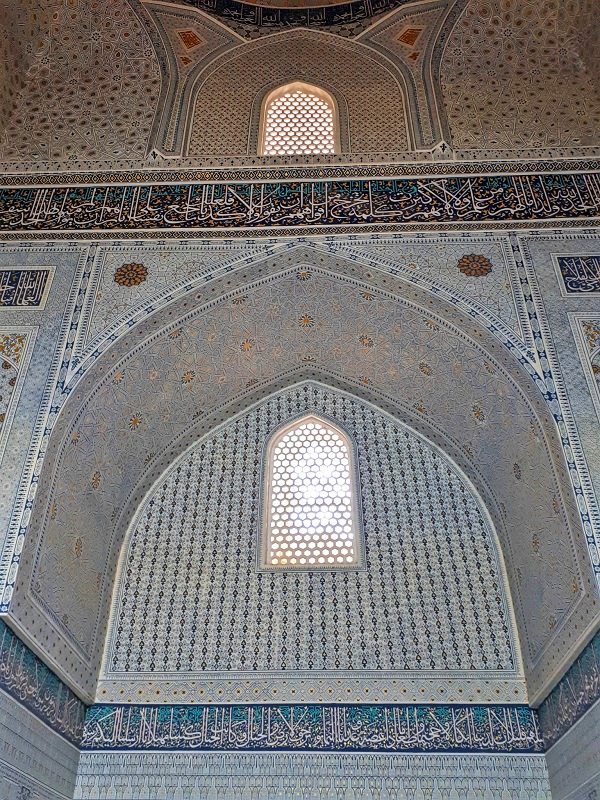

Upon passing through the main gate, you will find yourself in the inner courtyard, where the entrance to the main building, which is adorned with a breathtaking blue dome, awaits.

The hallway and first few chambers are very modest with little to no decorations.

You will encounter several information signs that offer an overview of Amir Timur’s life and military accomplishments.

To the right, a door leads to the main chamber of the mausoleum beneath the dome, which is exquisitely adorned with blue tiles and golden decorative elements reminiscent of the interior of the Tilla-Kari Madrassa.

The mausoleum features some elaborate Muqarnas, a honeycomb-like type of vaulting typical for Islamic architecture.

The tombs of Timur and several of his sons and grandsons, including Ulughbek, appear remarkably humble.

However, you should note that these are not the actual tombs but rather the markers of them – something which is common for Muslim mausoleums.

In a crypt situated precisely beneath the markers lie the actual graves of Timur and his descendants.

Other mausoleums

In the immediate surroundings of the Guri Amir you can find several other historic mausoleums.

Just behind the Guri Amir Mausoleum is the seemingly forgotten Ak-Saray Mausoleum – which was unfortunately closed off for the public.

The nearby Rukhobod Mausoleum is believed to be the oldest in the city, dating back to 1380.

Lunch

As lunchtime approached, I decided to stop at a nice-looking restaurant on Registanskaya Street, one of the main streets in the historic city centre of Samarkand.

I opted for a meat and potato dish, which turned out to be highly generous in portion size.

The dish was garnished with a generous amount of onions and flavoured with lemongrass and ginger, creating a unique flavour.

Karimov

On my way to the next sights in town, I once again passed by Registan Square, where I noticed a couple capturing their wedding photos.

Even though it was a weekday, I was surprised by the large number of couples taking wedding pictures in the area.

Already in the 3rd century BC, when the city was still known as Marakanda, it was reportedly an affluent and cosmopolitan place.

Alexander the Great was the first of the great conquerors to capture the city, saying that Samarkand was “even more beautiful than I ever imagined”.

In the centuries that followed, Samarkand emerged as a pivotal stop along the historic Silk Road, facilitating the transport of goods between China and Europe through the trade caravans.

The park situated to the east of Registan Square was a popular spot for wedding photographers as well.

However, there wasn’t much to see in this park besides a colossal statue of Islam Karimov.

Karimov, who was born in Samarkand, ruled Uzbekistan with an iron grip from the moment the country gained its independence following the break-up of the Soviet Union until his death in 2016.

I continued down Tashkent Street, a leafy pedestrianised street, towards the next historic sight in town.

Bibi Khanym Mosque

The Bibi Khanym Mosque is the largest in Samarkand and makes for an interesting sight to visit.

It is named after Bibi Khanym, Timur’s Chinese wife, who is said to have commissioned its construction while her husband’s was away on a military campaign.

The Bibi Khanym Mosque, which was completed shortly before Timur’s death in 1405, must have been among the most magnificent architectural marvels of his empire at that time.

However, the grand design of the mosque proved to be its downfall, as the building collapsed in 1897 following an earthquake.

The mosque had been reportedly deteriorating for centuries before its collapse, as the ambitious design pushed the limits of medieval construction techniques.

However, thanks to a recent renovation project, the grand main gate building and several domes of the mosque have been restored.

Bibi Khanym Mausoleum

On Tashkent Street, directly across from the Bibi Khanym Mosque, stands the mausoleum where Timur’s wife, along with other influential women of the court, is buried.

What you see inside the mausoleum are again markers of the actual place in the crypt below where the women are buried.

Karimov Mausoleum

At the far northern end of Tashkent Street near the Hazrat Khizr Mosque is a more recent mausoleum, that of Uzbekistan’s former dictator Islam Karimov.

Even though photography is officially prohibited on the premises, I managed to discreetly capture a few shots of the mausoleum.

As the Karimov Mausoleum is located on a hilltop, you have some good views back over the Bibi Khanym Mosque.

Shah-i-Zinda

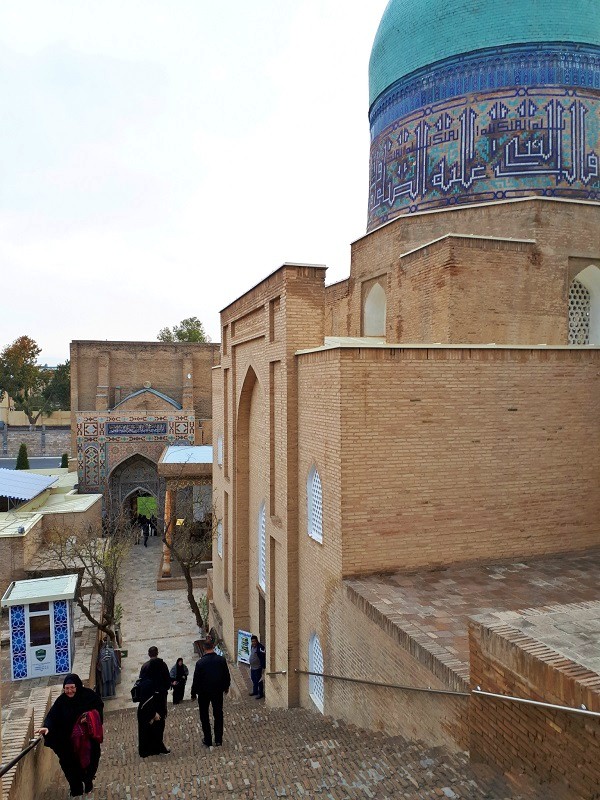

I had one major site left to visit on my Samarkand trip: The Shah-i-Zinda necropolis.

En route to Shah-i-Zinda, I passed an old graveyard that provided stunning views of Samarkand, with the Bibi Khanym Mosque and the three Registan madrassas clearly visible.

The Shah-i-Zinda, meaning “Living King,” is a vast necropolis consisting of around 20 mausoleums, each constructed in various years over the course of eight centuries.

The name Shah-i-Zinda originates from a legend surrounding a nephew of Prophet Muhammad, who is believed to have miraculously survived beheading when he arrived in this area to propagate Islam.

Interconnected by arched passageways, the Shah-i-Zinda complex is divided into three parts: A lower, middle, and upper part.

Exploring Shah-i-Zinda

When I entered the Shah-i-Zinda complex I initially thought it was a bit underwhelming after my prior visit to the great Samarkand sights of the Registan, Bibi Khanym Mosque and Timur’s Mausoleum.

Oh boy, was I wrong!

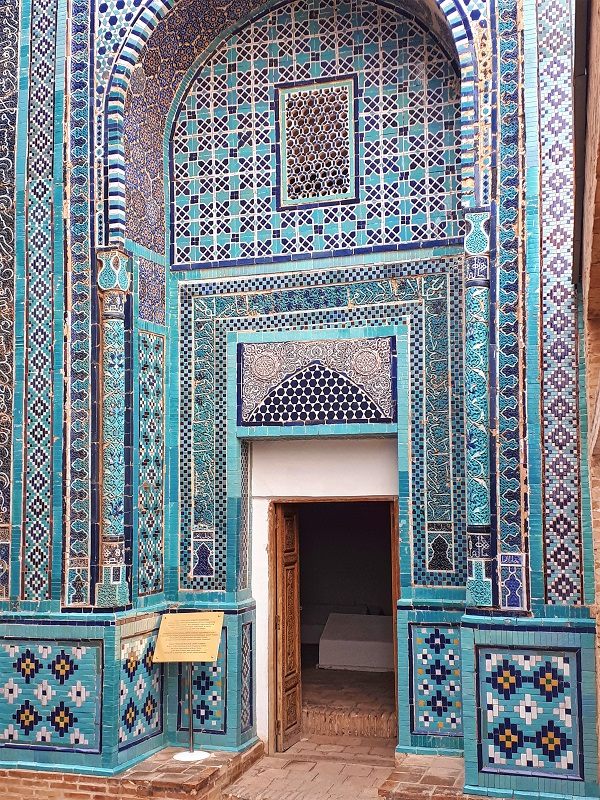

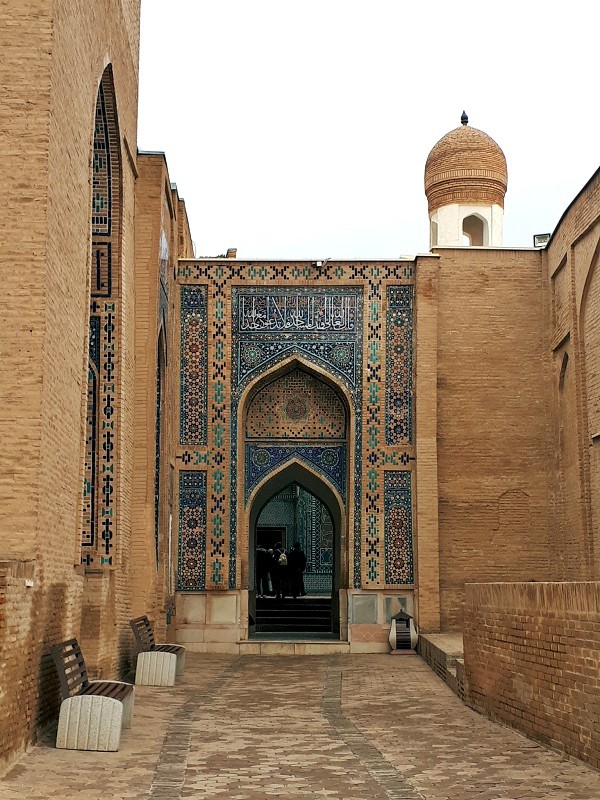

Although the lower part of the Shah-i-Zinda complex isn’t the most impressive, the rather plain brickwork soon gives way to stunningly decorated mausoleums with perhaps even more colourful tilework and impressive domes than the madrassas of the Registan.

The Shah-i-Zinda is an absolute stunner of a sight and should really not be missed when you visit Samarkand.

Different mausoleums

There are lots of different mausoleums you can visit at the Shah-i-Zinda in Samarkand, each decorated in different colours and patterns.

Even though some of you might have gotten a bit tired by now of all the tiles and domes, I certainly wasn’t as I couldn’t get enough of it during my Samarkand trip.

I just absolutely adore the architecture, calligraphy and beautiful colours of Samarkand’s historic buildings.

Mosque

At the Shah-i-Zinda complex, I observed a group of veiled women praying in the functioning mosque during my visit.

In Uzbekistan, despite being nominally Sunni Islam like other Central Asian countries, conservative religious practices are generally discouraged and sometimes even suppressed in the secular nation.

Under the Karimov regime, the government imposed limitations on the number of Muslims permitted to undertake the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, and the intelligence services closely monitored every mosque and sermon across the country.

Quite some people considered to be too fundamentalist, whether or not they were indeed supporting jihadist groups as the authorities feared, or might just have been very pious and conservative, were even arrested.

Uzbekistan has long been concerned about the threats of terrorism and radicalisation, although these problems are primarily confined to the conservative Fergana Valley region.

Although the question of whether repression effectively resolves the situation or potentially fuels more hatred and radicalisation is subject to debate, the new Uzbek president Mirziyoyev was however considering loosening some religious restrictions when I visited the country.

Back to the hotel

On my way out of the Shah-i-Zinda complex, I took the opportunity to visit some of the mausoleums that I had bypassed on my way in.

It is truly worth taking the time to explore each and every one of them, as they all have different designs and some are just absolutely breathtaking.

As dusk settled in, I grabbed a quick bite of kebab from a local eatery and purchased a few bottles of beer from a nearby liquor store near the Registan to enjoy in the comfort of my hotel room.

The friendly guys at the alcohol store even gave me two complimentary mini bottles of (very decent!) Uzbek vodka as a gift.

Samarkand hotel

On my trip to Samarkand I stayed at Furkat Guest House.

For just $18 per night, this budget hotel turned out to be a decent and highly interesting choice.

The location of the hotel was superb as it was just a 5 to 10-minute walk to the Registan.

Although my room itself was comfortable, it certainly wasn’t the most charming ever and was a bit weirdly furnished.

Besides, the Wi-Fi internet was extremely spotty and only worked when I was sitting right next to the door.

Furkat Guest House however excelled when it came to hospitality as the owner was amazingly friendly and eager to talk, while the breakfast buffet served on a large communal table was lavish and full of fresh local produce.

Conclusion

I had eagerly anticipated my trip to Samarkand as I had always longed to visit this historic city in Uzbekistan.

Fortunately, my experience visiting Samarkand easily exceeded my high expectations.

Samarkand was such a joy to explore and its architecture is so magnificent that it easily ranks along the top five most beautiful places I’ve seen across the world in well over 80 different countries.

The Registan is undoubtedly the most awe-inspiring sight in Samarkand, although the Bibi Khanym Mosque, Timur’s Mausoleum and particularly the Shah-i-Zinda also possess a remarkable beauty.

If you have a fascination for history or a deep appreciation for Islamic art and architecture, I highly recommend making the effort to visit Samarkand.

Trip report index

This article is part of the ‘From Uzbekistan With Plov‘ trip report, which consists of the following chapters:

1. Review: Prietenia Night Train Bucharest to Chisinau

2. Chisinau Guide: A Visit to Moldova’s Capital

3. Istanbul Ataturk Airport and the Turkish Airlines Lounge

4. Review: Turkish Airlines Business Class Airbus A330

5. Tashkent Travels: A Day in the Capital of Uzbekistan

6. Tashkent to Samarkand by Uzbekistan Railways ‘Shark’ Train

7. Samarkand Visit Guide: Travelling Through Silk Road Splendour (current chapter)

8. Review: Afrosiyob High-Speed Train Samarkand to Bukhara

9. Bukhara: Exploring Unique Historic Sights and Timeless Charm

10. Bukhara to Khiva by Train: My Travel Experience

11. Khiva: Uzbekistan’s Unique Desert Oasis City

12. On a Night Train Across Uzbekistan: From Urgench to Tashkent

13. Guide: How to Travel From Tashkent to Shymkent

14. Shymkent: The Gateway to Southern Kazakhstan

15. Sukhoi Superjet: Flying Russia’s Homemade Plane