A Tribute to Mariupol: Memories of a Pre-War Visit

This trip report tells the tale of my visit to Mariupol in Ukraine’s Donbas region just weeks before the Russian invasion and the outbreak of full-scale war.

Tribute to Mariupol

I have struggled for a while thinking how I would write down my experiences visiting Mariupol just a month before the Russian invasion.

As most of my readers undoubtedly know, the city has almost been completely destroyed by the invading Russians.

It is estimated that tens of thousands of innocent civilians have been killed in Mariupol, although some insiders say the number is as high as 100,000 deaths in a city which had a peacetime population of 425,000 inhabitants.

Associated Press journalists Mstyslav Chernov and Evgeniy Maloletka were in Mariupol during the Russian siege and documented the death and destruction around them.

It’s an absolute must to read their harrowing stories and see their pictures of the destruction of Mariupol if you haven’t done so before as their work is Pulitzer Prize and World Press Photo Award-worthy.

When writing about Mariupol it’s hard not to think about the city’s destruction and Russian war crimes.

However, by solely focussing on all the devastation it’s easy to forget about what Mariupol once was: A beautiful, happening and proud Ukrainian city whose inhabitants certainly did not ask for any kind of Russian interference with their lives.

This trip report is therefore mostly a tribute to the great city of Mariupol and its people.

I hope that one day people will again be able to visit a liberated and fully rebuilt Mariupol so they can enjoy the city as much as I did.

Mariupol train

I had arrived in Mariupol by taking the train from Rakhiv in the west of Ukraine – an epic 29-hour-long journey covering 1806 kilometres which back then was the country’s longest train route.

When I disembarked the train and set foot on the platform it certainly felt surreal to finally be in Mariupol.

After all, in the prior weeks there had been a significant Russian military build-up all along the Ukrainian border.

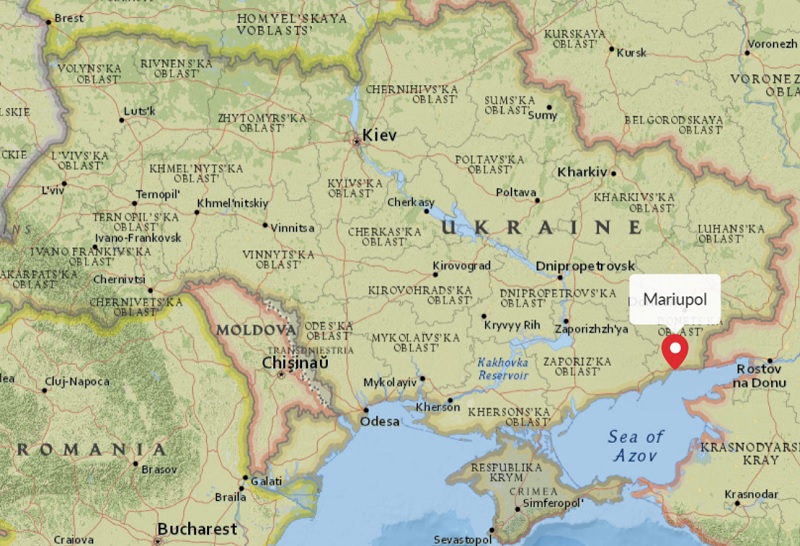

It was clear from the start that Mariupol, located in the industrial Donbas region just miles away from the border with Russia, would bear the brunt of a full-scale military invasion.

However, I also knew that war would not suddenly start in the next few days while I was in town, as there were no signs yet of the necessary final invasion preparations such as units being deployed to forward staging points and field hospitals being set up and activated.

I therefore knew that I would be safe in Mariupol, although I couldn’t help to think during my visit about what was surely to come in the near future.

That said, as much as I expected the Russian invasion to happen, the sheer amount of destruction and violence levelled at innocent civilians was something I couldn’t envision.

An evening walk

Having checked in at my hotel, I started with an evening walk through the city centre of Mariupol.

One of the first things I noticed walking the streets of Mariupol was the distinct smell in the air, probably from the iron and steelworks based in this city.

You can already see the flames and fumes from the steelworks as you approach the city by train.

Despite the thick air I found Mariupol to be a highly pleasant city the moment I set foot in it.

The city centre streets and buildings were beautifully illuminated at night and looked well-kept.

One of the first sights I came across was the old water tower, which is one of the symbols of the city of Mariupol.

The nearby drama theatre only became a symbol of Mariupol during the war after the Russians bombed it while hundreds of children and women were sheltering inside.

Even though the local population clearly designated the theatre as a humanitarian shelter by writing the word “deti” (дети – Russian for “children”) in front of the building, the Russians still attacked it in what can only be described as a horrific war crime.

#Mariupol Theatre – this time last year and now, following Russian "denazification". The wickedness visited on #Ukraine by Russia can never be forgiven, forgotten or negotiated away. The only acceptable outcome is a full Ukrainian victory. pic.twitter.com/7NRQKUM2GP

— Daniel Hamilton 🇺🇦💪 (@danielrhamilton) December 19, 2022

A Mariupol night out

Mariupol felt like a lively city as there were plenty of people out on the streets.

It was certainly a diverse crowd too, as parents were taking a stroll with their children, youths were hanging out on the streets with a beer in their hand and immaculately dressed people were preparing for a night out in town.

With plenty of appealing cafés, good restaurants and fun pubs to choose from, Mariupol certainly had all that was needed for a fun night out.

I headed straight for a restaurant called Sufra, which did some excellent Georgian food.

Hotel

After the excellent meal I walked a bit more around the city centre before retreating to my hotel.

I was staying at Hotel Reikartz, which seemed to be the business hotel of choice in Mariupol.

Indeed, the next morning there was quite an international crowd at the breakfast buffet, with even two teams of foreign TV journalists being present, preparing for their reports in the city that day.

Market visit

I started off my day with a visit to Mariupol’s Central Market (Tsentralʹnyy Rynok).

With the exception of the local pubs and coffee houses, there is no better place than a market to get an idea of the talk of the town and to assess the state of mind of the people.

Mariupol’s main market certainly didn’t disappoint as it is sprawling, colourful and full of people out to do their shopping.

Although the market is just a couple of hundred metres away from the city centre, it felt like an entirely different part of town.

While the city centre is extremely well-kept, some of the streets around the Central Market were rather dilapidated.

Most of the shoppers seemed to be old babushkas and middle-aged people from a working class background.

After all, Mariupol is in essence an industrial city, with the Azovstal and Ilyich Iron and Steelworks (both owned by Ukrainian billionaire Rinat Akhmetov) being the largest employers.

Inside the Central Market

Despite being located in a dangerous corner of the country just a stone throw away from the border with Russia, the people in Mariupol tried their best to go on with life as normal as possible.

Most of the people I spoke to inside the market said they were not that worried about the Russian military build-up and invasion threats.

It appeared that there were two reasons behind this thinking.

First of all, the Russian threat was not completely new to the people of Mariupol as almost a full decade of low-intensity war has been raging in the Donbas prior to the full-scale Russian invasion of February 2022.

Secondly, daily life was already challenging enough for many people in Mariupol, who were trying hard to make ends meet.

In 2014, heavy fighting broke out in Mariupol between Ukrainian government forces and Russian-backed militants belonging to the separatist Donetsk People’s Republic.

Although the city of Donetsk and large swathes of Donetsk Oblast fell under control of these Russian separatists, Ukrainian forces did eventually manage to chase them out of Mariupol in June 2014.

When I visited Mariupol, the line of contact between Ukrainian soldiers and the pro-Russian separatists was located some 20 kilometres east of the city near the town of Shyrokyne about halfway towards the Russian border and had been stable for the last few years.

It seemed that most people just couldn’t fathom how much worse the situation could possibly get or simply had other worries on their mind.

Exploring the market

I still tremendously enjoyed my visit to the Central Market.

Mariupol’s Central Market exists out of a large Soviet-era main market hall and a maze-like patchwork of alleys with hundreds of shops and stalls around it.

Inside the main market hall you can find dairy and meat products on the ground floor and shops selling bridal and gala dresses on the first floor.

Outside, shops and stalls were grouped together by category too, with one part of the market being set aside for fruits and vegetables, while other parts were occupied by clothes and shoe stores.

Old world charm

When strolling around the streets to the east of the Central Market you can get a great glimpse of some of the old world charm of Mariupol.

Although many of these wonderful pastel-coloured or red brick buildings from the Tsarist era are in a rather decayed state, they still show the rich history of the city.

Mariupol has always been an important port city throughout history.

The port and all the trade links turned Mariupol into a thriving, multicultural city which was home to Ukrainians, Russians, Cossacks, Jews, Tatars and Pontic Greeks alike.

Theatre square

Having explored the area around the Central Market, I headed back towards the city centre to see the area in broad daylight.

The main street of Mariupol is Peace Avenue (called Prospekt Myru in Ukrainian), which runs from the mouth of the Kalmius River and the Azovstal complex in the east all the way to the western outskirts of the city.

In the heart of the city centre, Prospekt Myru basically forms a giant roundabout with a park in the middle.

This park is called Theatre Square and besides the now-destroyed drama theatre it also features a fountain and playground.

Theatre Square is a beloved place for the citizens of Mariupol to take a stroll and when I visited during winter it had a large ice rink as well.

The architecture in the city centre is certainly different too than the neighbourhood I walked through before, as Theatre Square is lined by stately Soviet-era buildings.

The buildings at some corners of the square are completely symmetrical – which is quite typical for Soviet architecture.

When the Russian Army occupied Mariupol on 20 May 2022 after a long and bloody siege, the invaders renamed Prospekt Myru to Prospekt Lenina (Lenin Avenue), which should already tell you enough about their genocidal intent.

Greek Square

From the drama theatre I headed towards Gretska Ploshcha (Greek Square) in the western part of the city centre.

The name of the square is a testimony to the ancient Greek origins of Mariupol.

Mariupol is still the city in Ukraine with the largest (Pontic) Greek minority at 5% of the (pre-war) population.

Some of the buildings around Greek Square sustained heavy damage during the fighting between Ukrainian government forces and Russian separatists in 2014.

The Mariupol City Hall on the southern side of this square even burned out completely and has been an empty shell ever since.

Primorsky Park

As Mariupol is an important port city, I couldn’t leave the city without a visit to the seaside.

There are a few different places where you can enjoy sweeping views over the Mariupol coastline and the Sea of Azov, the shallowest sea in the world with an average depth of only 7 metres (23 ft).

One of these places with fine views over the Sea of Azov is Primorsky Park (Seaside Park), located in the suburb of the same name towards the south-west of Mariupol’s city centre.

The walk towards the park entrance was a surprisingly interesting one as I passed along some old Soviet war memorials and brutalist architecture.

At the entrance of Primorsky Park you can find one of such monuments, which is dedicated to the Red Army soldiers who liberated the Donbas during World War II in the year 1943.

Towards the left side of the park entrance stands the modern Illichivets Indoor Sports Complex, although this sadly is one of the many civilian buildings in Mariupol which has been destroyed by the Russians during the siege.

Primosky Park isn’t the best maintained nor the most beautiful park as it seemed to exist mostly out of potholed pavement.

However, once you reach the end of the park you will find yourself standing high on a bluff overlooking the Sea of Azov.

The ubiquitous “I love Mariupol” sign (written in Cyrillic letters as “Я ♡ Маріуполь”) at the cliffside seemed to be a popular photography spot among the Ukrainian locals visiting the park.

Mariupol geography

Mariupol’s geography is quite special as at some points the sea appears to be close by, but in reality is still a long walk away.

Primorsky Park is an excellent example of this.

If you stand on top of the bluff here, the seashore isn’t far away as the crow flies.

However, as there is no path down the bluff towards the sea, you can’t get directly get there and have to take a big detour to one of the few places in Mariupol where you can actually descend all the way down to the shoreline.

This is not unique to just Mariupol, as you can find a similar geography in other coastal areas of Ukraine such as Odessa where most of the city is built as well on top of a bluff directly behind the coastline.

As I still wanted to actually wade in the Sea of Azov, it meant that I had to walk all the way back from Primorsky Park to the city centre of Mariupol in order to descend towards the shoreline from there.

On my way back, I stopped for a few minutes to pet some stray cats, who fortunately seemed to be well taken care off by the locals as they had some bowls with food and water.

Thinking back about those cats I however can’t help but wonder how many pets or stray animals have died or have been left behind to fend for themselves during the war.

Death warrants

Taking a different route through the city centre, I encountered some more Mariupol landmarks on my way to the seashore.

One of these beautiful city centre buildings houses Mariupol’s Pryazovskyi State Technical University, which sadly enough sustained quite a lot of damage as well from random Russian shelling and bombardment.

This university building started its life in 1911 as the Diocesan Women’s School, although it was quickly closed after the communist revolution.

The Nazis used it as their headquarters during their occupation of Mariupol, sending out the death warrants of thousands of Jews living in the wider Azov region from here.

Most of these local Jews were shot in the Agrobaza trenches – with some of them even being buried alive.

Nearby, the magnificent Mariupol Philharmonic Hall with its large statue of Alexander Pushkin is nowadays the venue of choice for arbitrary justice and sham trials.

The Russian occupiers of Mariupol use this concert hall to try captured POWs and have even constructed cages inside for their show trials.

Mariupol, the local technical university building.

The city of my years as a student.

This is Europe, the year is 2022. pic.twitter.com/TFJj8qWkbh— Illia Ponomarenko 🇺🇦 (@IAPonomarenko) March 9, 2022

Train tracks

In order to reach the seashore and the beaches of Mariupol you still have to cross a railway line which runs directly alongside the sea.

From the pedestrian overpass you have a great view over the railway tracks and Mariupol’s city beach on the Sea of Azov.

Dozens of empty passenger train wagons were parked at the sidings, although it seemed that many were just abandoned and collecting rust.

City beach

Although my Mariupol visit was in the middle of winter, it was perfect weather for a nice walk on the beach.

Despite the fact that the temperature was hovering around the 0° Celsius mark (that’s 32°F for my friends across the Pond) and it was rather chilly when facing the wind head-on, the weather was actually quite pleasant when sitting down in the sun away from the wind.

I was certainly not the only one taking a stroll on the beach, as dozens of locals had the same idea.

Ukrainisation of Mariupol

The most popular spot at the beach was a brand new pier jutting out into the sea.

This pier was one of the most recent urban developments in Mariupol and certainly felt like a rather nice place to wind down.

Mariupol has always been a predominantly Russian-speaking city, although don’t let this fool you by thinking that it equals support for Putin or the Russian annexation of large swathes of Ukraine (don’t forget that Ukrainian President Zelenskyy is a native Russian speaker).

On the contrary, since the start of the conflict in the Donbas in 2014, Mariupol has actually “Ukrainised” according to most of the locals I talked to during my visit.

They said that since the start of the conflict both local and national Ukrainian institutions grew stronger and more efficient while people became increasingly distrusting of Russia’s ulterior political motives.

This strengthened the bond and trust levels between the locals and the Ukrainian government.

Sure, many of the locals were certainly not happy with everything that was done and decided in Kiev such as the introduction of far-reaching language laws, but if you would ask around they would all still prefer the imperfect Ukrainian democracy above a Russian dictatorship.

Indeed, in the years prior to the Russian invasion of February 2022, Mariupol actually underwent some kind of a renaissance as people flocked to the city from other parts of the Donbas and new investment was pouring in, which translated into city regeneration projects and a cultural resurgence.

Although part of this was a government-driven effort, it also happened as an indirect result of the conflict in the Donbas as irony would have it.

With the regional capital of Donetsk being occupied by Russian separatists, Mariupol suddenly became the de-facto regional centre of Donetsk Oblast and grew in importance.

However, at the same time commercial life became more difficult in Mariupol as the main railway line to the rest of Ukraine through Donetsk was severed and the Kerch Strait which connects the Sea of Azov to the Black Sea was suddenly controlled by Russia after they invaded and annexed Crimea in 2014.

Cherry liqueur

It was nice to see that the Mariupol Pier had a branch of Pyana Vyshnia, the well-known cherry liqueur bar which originated in the western Ukrainian city of Lviv.

Of course, I couldn’t resist a cup of the cherry drink.

Although you can drink it chilled as well, in cold winter weather like this the cherry liqueur is typically served mulled.

City Garden

Having visited the beach, I headed back uphill towards the city centre.

This time, I took an alternative route by climbing the steps towards the City Garden, another important Mariupol park.

The City Garden, which has a semi-circular entrance arch in Neoclassical style typical of so many other parks throughout the former Soviet Union, is certainly worth a stroll.

At the far end of the park you overlook the coastal bluffs and have some great views over the Sea of Azov and the Azovstal complex in the far distance.

Pre-revolutionary Mariupol

In the neighbourhood directly around the City Garden you can get some more glimpses how Mariupol used to look like in pre-revolutionary times before Ukraine was absorbed into the Soviet Union.

Unfortunately, many of these buildings are either abandoned or badly decayed.

This is for example the case with a lovely Art Nouveau mansion designed by Viktor Alexandrovich Nielsen in the early 20th century.

Nielsen, who was the Mariupol’s city architect from 1901 to 1917, used to live himself in this house until the Bolsheviks appropriated the property.

The mansion was named the House of the Weeping Nymphs by Nielsen as it was built in memory of his deceased daughter.

Food

Back in the city centre it was time for one last meal in Mariupol.

I ended up having a late lunch at a restaurant called Sherwood, which had an appealing menu and some good online reviews.

The restaurant staff was certainly welcoming and my Solyanka soup as starter was good.

However, the same could not be said of the grilled mussels and cheese.

About halfway through my meal it suddenly tasted a bit off, so I decided not to eat the rest of it.

Unfortunately, damage was already done as I was about to find out later that evening on the train out of Mariupol.

Choral Synagogue

After the meal I still had some time left before the departure of my train.

I therefore decided to explore some of the neighbourhoods towards the east of the city centre to see if I could find something interesting there.

That was indeed the case, as I stumbled upon the ruins of a synagogue.

Mariupol’s Old Choral Synagogue was constructed in 1882 and was one of the five Jewish houses of worship in pre-revolutionary Mariupol.

It was expropriated by the Soviets during an anti-religious campaign in the 1930s, although unlike some Catholic and Orthodox churches in Mariupol it was spared from destruction.

The Choral Synagogue even survived the Nazi occupation, as instead of destroying the building the Nazis used it as a hospital and assembly point.

After the liberation of Mariupol, the Soviet regime used the building as a gymnasium and art gallery but when the roof collapsed in the 1990s after heavy snowfall, the Choral Synagogue was left to the elements.

The Synagogue ruins currently houses an exhibition about the Holocaust, with a memorial plaque showing the names of more than 6,000 local Jews who were murdered by the Nazis and pictures of some local residents who were recognised as “Righteous Among the Nations” by Yad Vashem for helping to save Jews during World War II.

Mariupol. Left, a picture I took on 22nd January. Right, a recent picture of how the same street corner looks now. Seeing such images still comes as a shock each time. pic.twitter.com/gXsX0auqdV

— Paliparan (@PaliparanDotCom) April 8, 2022

Azovstal

If you walk from the city centre of Mariupol towards the east, you will eventually reach a point where you can walk no further.

A railway line and the River Kalmius separate the city centre of Mariupol from the eastern suburbs and the Azovstal iron and steelworks.

Although there is a bridge further to the north which crosses the railway tracks and river, I didn’t have the time to take this road to have a closer look at the huge Azovstal complex.

Of course, Azovstal would later become well-known across the entire world for being the last holdout of Ukrainian defence forces in Mariupol.

The massive industrial complex – which has a large system of underground tunnels and bunkers built in the Soviet-era – was a natural defensive bastion.

It took the Russians months to finally conquer Azovstal and the city of Mariupol and the heroic Ukrainian defence bought invaluable time for Ukrainian forces elsewhere to build up defences and to prepare for counter-offensives.

Eastern neighbourhoods

From the outer edges of the Azovstal complex I headed back towards the train station on Persha Slobidka Street.

This took me through yet another lovely neighbourhood full of old houses and mansions from the Tsarist era.

One of the most interesting buildings I encountered was Dr. Gamper’s House, a neo-Gothic mansion named after Sergey Fyodorovich Gamper, the chief doctor of the Mariupol hospital.

When communists took over the city, the house was expropriated and turned into a communal property for several families.

The 1970s train station of Mariupol looks certainly a bit out of place when you compare it to the old world architecture from the surrounding neighbourhood.

Mariupol certainly felt like a city of contrasts – and I really came to love it during my short visit.

Conclusion

For many different reasons, the city of Mariupol will always have a special place in my heart.

During my Mariupol visit I quickly discovered how thriving and full of energy the city was.

Although life was certainly not easy for lots of people in Mariupol even before the outbreak of war, it felt like the city was on the rise.

There were some new urban developments, a vibrant café and restaurant scene and even a bit of optimism despite the difficult economic times and the geopolitical problems.

Even though Mariupol has always been a predominantly Russian-speaking city, Ukrainian institutions and ties with Kiev actually grew stronger in the decade before to the invasion of 2022 and the outbreak of full-scale war.

Moreover, Mariupol actually turned out to have a fascinating history.

Although many old buildings and neighbourhoods were either decayed or even completely abandoned, you could still get a great sense of how Mariupol used to look like in the days of the Tsarist Russian Empire.

Seeing the images of a destroyed Mariupol and the Russian brutality and war crimes is painful even for me – and I certainly can’t even begin to comprehend how it must be for the people who have fled the city or those who still live there now in the ruins.

I hope that one day Mariupol will again be part of a free and fully liberated Ukraine.

When it is, I will certainly come back to visit Mariupol again.

Trip report index

This article is part of the ‘Mail From Mariupol: A Pre-War Trip to Ukraine by Train‘ trip report, which consists of the following chapters:

1. Review: Night Train Bucharest to Sighetu Marmatiei, Romania

2. At the Sighet-Solotvyno Border: From Romania Into Ukraine

3. Review: Solotvyno to Rakhiv by Bus

4. Review: Hotel Europa, Rakhiv, Ukraine

5. In the Land of the Hutsuls: A Visit to the Town of Rakhiv

6. Rakhiv to Mariupol: Riding Ukraine’s Longest Train Route

7. A Tribute to Mariupol: Memories of a Pre-War Visit (current chapter)

8. Ukrainian Railways Mariupol to Kiev Train in Platzkart

9. Review: Ibis Kyiv Railway Station Hotel

10. Review: Kyiv-Pasazhyrskyi Station First Class Lounge

11. Ukraine Night Train: Over the Mountains to Mukachevo

12. Review: Latorca InterCity Train Mukachevo to Budapest

13. A Short Stopover in Szolnok, Hungary

14. Review: Ister Night Train Budapest to Bucharest

15. Epilogue: Witnessing the Ukrainian Refugee Crisis at the Border